Port Lands Watch: Why Waterfront Toronto is building a new mouth for the Don River

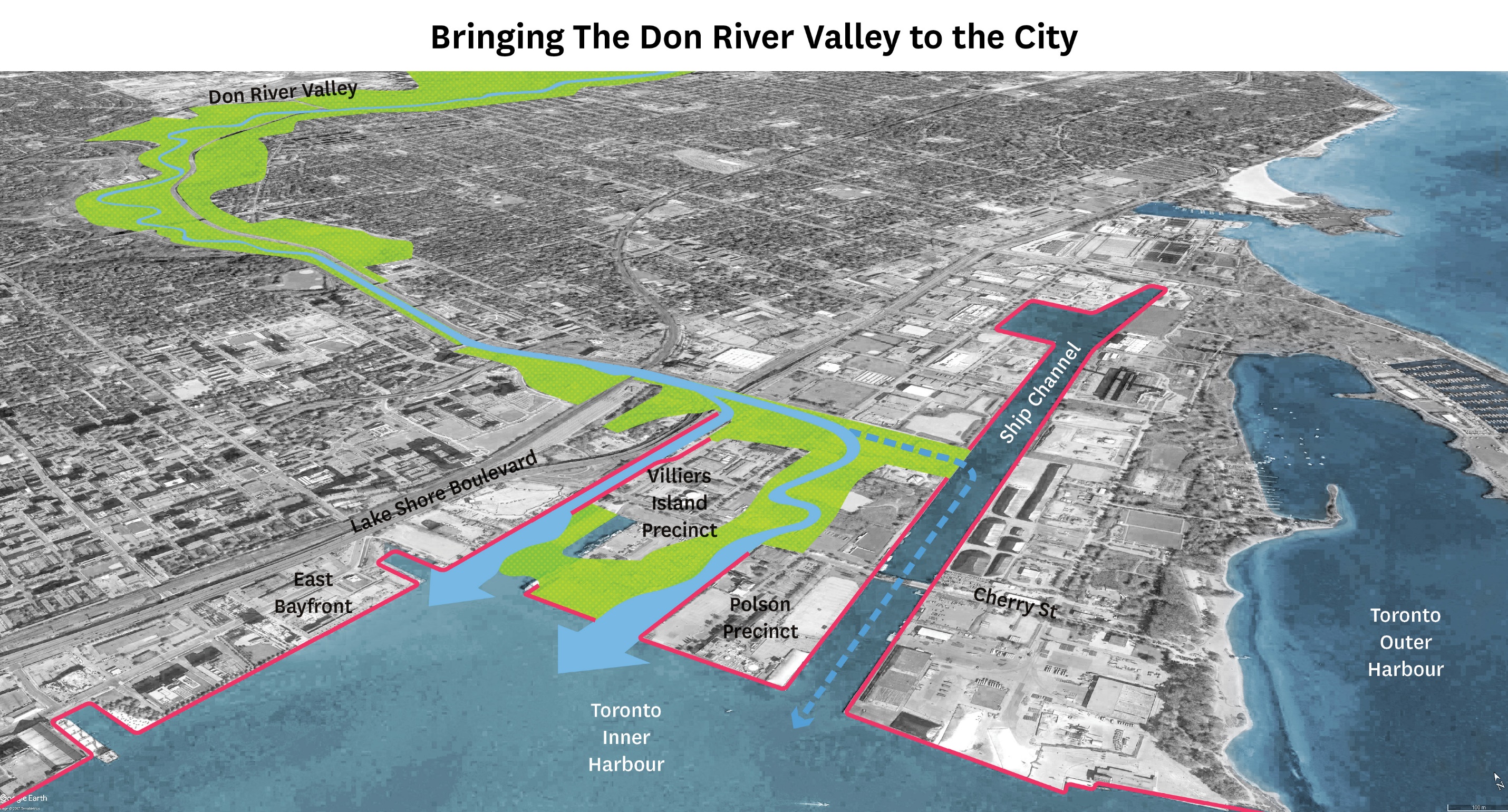

In part two of our series on the evolving Port Lands, we look at flood protection on Villiers Island and its surroundings.

A lot of talk in the Toronto urban planning community (including our first piece in this series) focuses on the new Villiers Island neighbourhood, but you might be surprised to hear that it doesn’t actually exist today. And before it can happen, a lot of key work needs to be completed.

When the Port Lands were first developed, the Don River was diverted into the Keating Channel, which travels directly west and eventually meets Lake Ontario. The hard 90-degree turn makes it very difficult for water to flow, and causes it to back up into the valley, particularly during heavy rain events.

Given the severity of flooding and the risk to the substantial infrastructure located along the foot of the Don River — including the Don Valley Parkway, the GO Transit rail and streetcar routes in the area, and soon the Ontario Line — a mitigating solution was overdue for years. Just last February, the Don River spilled over its banks and flooded the lower Don River Trail.

But the overdue plan is in and underway. Waterfront Toronto’s solution is a new mouth for the Don River to drain into Lake Ontario, with additional flood-protection measures to boot.

Read on for a breakdown of just what that entails.

The new river mouth

A new river mouth might sound pretty simple — it’s basically just a big ditch, right?

Well, no. The new mouth is being created so that water can flow past the existing turnoff to the Keating Channel, and then take a more natural turn once it passes south of Commissioners St. From there, the water will wind west to Lake Ontario, cutting Villiers Island off from the land south of it.

This path has been designed to naturally slow the water while also accommodating a much larger volume thanks to its gradual sloping banks. The work began in December 2017, and is set to be completed in 2024.

In the past year, progress has advanced significantly — plantings have occured and water has begun to accumulate in the river valley. While many imagine the “flooding” of the new river valley as a dramatic event with water rushing and dams breaking, the reality is it will happen much more slowly.

The slow flooding of the valley ensures new plant growth is not swept away or damaged, and allows any issues to be dealt with before water becomes a permanent feature. Once the valley has been slowly filled, only then will the “dams” at the south and then north end of the new valley be removed.

It’s also important to note this current plan reflects a change in the way water management infrastructure tends to be designed — in the 20th century, concrete channels were all the rage. These work well for moving water somewhere else quickly, but they aren’t effective for actually accommodating more water.

So Waterfront Toronto has opted instead for a naturalized river valley. That means planting appropriate plant species along the river to both create drag on the water as it flows over them and help absorb it.

Of course, keeping the plant life in check means attracting various species of birds, fish, and amphibians, all of which require specialized types of habitat to survive. This creates varying design characteristics and requirements for the new river, from pools of varying sizes at the river’s edge to dead logs for shade to perches for birds.

Fortunately, as works on planting native species have progressed and as habitats have started to collect water, all manner of native species have begun moving into the area.

Finally, more water-absorbing and filtering plant species have been placed along the edges of the river to accommodate the worst storm surges and allow overflow into the surrounding wetlands. This process also includes the use of levees — usually topped with walking trails — situated between the main river and the newly created wetlands.

These efforts naturally create more interesting parks and public spaces for people to enjoy, all while protecting developments in the area from floods.

Planning for variables

With winters growing more extreme, ice on the river also needs to be taken into consideration. For one, too much ice could dam up the river valley and lead to flooding, while hard ice that gets pulled through the valley could end up damaging the plants and shoreline.

To help with this, boulders known as armour stones as well as more dead trees have been used in areas with high volumes or fast flowing water to protect the surrounding environment.

It’s also important to consider how the river will interact with different water levels, from the water still entering the Keating Channel to the overflow water from the main valley that the wetlands will need to accommodate.

To handle this variability, a third “exit” for water from the Don is being built. This exit, which sits directly south of the old Keating Channel turnoff, will spend most of its time as a vibrant wetland. But in the most severe storm events — think Hurricane Hazel — it will allow water to flow overtop of it and into the shiping channel.

Of course, new bridges are required to cross these new waterways, and they’ve already been installed across the Keating Channel at Cherry St., as well as over the new river valley further south along Cherry, and at Commissioners St.

Work on realigning Cherry St. is currently wrapping up with the new road and bike lanes paved, and the new Cherry St. north bridge likely to open soon.

Welcome to sponge city

Additional passive elements included in the design will further protect new development in the area and the city more broadly from flooding.

This infrastructure often falls under the design principle of “sponge cities,” which is the practice of trying to absorb and handle water in place rather than simply moving flood problems somewhere else. These measures will include everything from permeable paving that allows water to seep through to bioswales — large planters with rocks to help prevent erosion.

Another such design feature is “green” streetcar tracks (already seen on the Eglinton Crosstown), which are surrounded by soil with plantings that act as a sponge, reduce the urban heat island effect, and even help reduce wheel noise.

The land itself is also being reshaped. Developments and infrastructure on and around Villiers island — perhaps most notably the footings on the new bridges — have all been raised to better protect from high water levels.

Addressing the bigger problem

Toronto, being a city that is more than two centuries old, was originally built with a combined sewer system. That means that flood water, rain water, and regular sewage is all combined in single pipes.

This usually isn’t an issue, as most water in the sewer needs to go to water-treatment plants, and the pipes can easily handle a small amount of rain water. But during extreme flooding, the high volumes of runoff can overwhelm the system. This forces a mix of mostly harmless rainwater and quite possibly harmful sewage to be released into rivers, creeks, and Lake Ontario, significantly reducing water quality.

Fortunately, something is being done. The Coxwell Bypass Tunnel is being built under the Don Valley using a tunnel-boring machine that would be right at home on a subway project, and is currently about 80 per cent complete.

This new super sewer will be connected to the Ashbridges Bay sewage plant, which is being upgraded and expanded to create more capacity, both for processing sewage and releasing treated water back into Lake Ontario. During extreme flood events, the tunnel and a series of massive circular access shafts located all over the valley — one of which is visible from the north side of the Bloor St. viaduct — will store the mix of runoff and sewage until it can be processed.

This will help improve water quality both in Lake Ontario and along the Don Valley and into the Port Lands. Plans call for constructing more tunnels in the future to add even more capacity.

Keep Digging

We hope you enjoyed the second piece in our four-part “Port Lands Watch.” If you missed it, we encourage you to check out the first piece in the series:

- Part 1: What’s up with Villiers Island?

- Part 3: How Villiers Island will work for Torontonians without cars

- Part 4: East Harbour and the future of Toronto’s eastern waterfront

Code and markup by Chris Dinn. ©Torontoverse, 2023