Why the Gardiner Expressway debate keeps coming back up

A look at the past, present, and future of a Toronto landmark and perennial hot topic.

Every city has its landmarks. In Toronto, for better or worse, the Gardiner Expressway is one of them.

Whether it’s the first glimpse of the Toronto skyline from the highway as it rounds Humber Bay, or the Blade Runner-esque landscape as it snakes through the mushrooming condos of the waterfront, the highway provides some of the city’s most memorable vistas.

At ground level, however, the vista is much less pleasant. For decades, Torontonians have lamented the crumbling concrete structure separating the downtown core from the lake.

As of 2016, there’s a plan in motion to rehabilitate the highway, but it has its detractors — and may factor into the upcoming mayoral by-election. Here’s what you need to know about the past, present, and future of this major piece of city infrastructure.

How did it get here?

The Toronto waterfront of the 1950s when the Gardiner was built was an industrial place, with acres of rail yards, port buildings, and warehouses handling goods moving in and out of the city. The shore functioned as a long utility corridor.

Other than a few spots such as the small amusement park and bathing pavilion at Sunnyside, which were built in the 1920s, no one would consider going for a stroll or having a picnic by the water.

As the Second World War ended, the vast industries that had been built to support the war effort shifted to civilian production. Automobile ownership exploded, and the city — like most other cities on the continent — developed a comprehensive plan for an expressway network.

The first two to be built — one along the lakeshore and one through the Don Valley — were the easiest since they required comparatively little demolition of existing neighbourhoods. Most of the Gardiner’s route was industrial, but the highway’s construction did result in the removal of the Sunnyside amusement park and some homes; it also cut off the once-elite Parkdale neighbourhood from the water.

When the expressway opened in 1958, it was one of many new elevated urban highways opening in Canada and the United States. It connected the downtown core to the Queen Elizabeth Way, one of the world’s first expressways that had opened in 1939 and previously ended at a big traffic circle near the Humber River (see map for visualization). It provided a quick route from the fast-growing new suburbs of Etobicoke and what later became Mississauga, and now moves over 150,000 cars per day.

Decades of plans

Not long after the highway was completed, people were already starting to see the harbourfront less as an out-of-the-way home for industry and more as one of the city’s potential major tourism and recreation destinations.

The vast rail yards were steadily shifted to the suburbs, and the central harbour was redeveloped by the federal government as Harbourfront Centre starting in 1972. The Gardiner was no longer part of a vast industrial landscape and instead was seen as more of a barrier to redevelopment.

Some looked to other cities, where ambitious projects to bury urban expressways were beautifying cities and freeing up land for redevelopment. While underground urban expressways are commonplace in places like Europe and Japan, many Torontonians looked to a closer example — Boston.

Unfortunately, Boston’s highway-replacement project, which took over a decade to build in the 1990s and came to be known as the “Big Dig,” didn’t provoke envy. Its gigantic cost overruns — more than double the initial budget and coming in, depending on how it’s measured, at as much as $20 billion (USD) — made expressway tunnels seem an extremely costly and risky idea.

In 2000, a report was released by the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Task Force, which had been appointed by all three levels of government to coordinate their efforts in the area. Nicknamed the Fung Report after the task force’s chair, Robert Fung, its most eye-catching recommendation was to demolish the Gardiner east of Strachan Ave., with traffic redistributed onto a re-landscaped Lake Shore Blvd. and an extension of Front St. to join with the highway near the Exhibition.

“The removal of the Gardiner Expressway deck is an essential step in creating a waterfront of international stature.” – Fung Report, 2000

The highway would have a short tunnel from Strachan to Spadina Ave. to provide capacity from the west to the busy Spadina interchange while eliminating the “boxed in” feel of Fort York.

In the end, this ambitious plan never came to fruition. Still, some sections of the Gardiner have already been demolished. Originally, the elevated roadway ran all the way east to Leslie St., but the segment east of Bouchette St. was demolished in 1999. Some of the former section’s pillars remain standing as a form of post-industrial public art.

In 2016–17, the loop offramp at Bay was also demolished to allow for the creation of the soon-to-be-completed “Love Park.”

What’s happening with the Gardiner today?

The Gardiner would now be old enough to collect CPP, and over six decades of freeze-thaw, road salt, and pounding traffic have taken their toll. The maintenance burden of the highway, especially its elevated section, has increased dramatically. The city needs to undertake constant repairs to make sure that the structure remains safe for traffic both above and below.

Check out this video for what the City had to do during the annual maintenance closure weekend in 2021 alone:

As a result, the City has developed an over-$2 billion comprehensive plan to bring the highway back to good condition. The central portion of the elevated highway is already undergoing rehabilitation, and the final segment will involve entirely rebuilding the concrete deck and steel girders among other improvements.

The segment east of Jarvis St., however, was the subject of significant debate. Since traffic on that section is far lower than it is further west, many advocates and political leaders argued that it should simply be demolished, traffic shifted to Lake Shore Blvd., and land freed up for development.

City Council opted in 2016 for a compromise “hybrid” proposal, currently anticipated for completion in 2030. The section east of the Don River would be demolished while the stretch from Cherry St. to the Don would be shifted north to run alongside the railway corridor, freeing up significant land for development along the Keating Channel.

The decision was controversial, particularly as its $1 billion price tag was roughly double the cost of demolishing the segment.

How will we pay for it?

The City has long sought alternative means of paying for the cost of upgrading the Gardiner and maintaining its other highways. In 2015, former Mayor John Tory proposed implementing road tolls on both the Gardiner and the Don Valley Parkway, but they were blocked by the provincial government, which feared a political backlash from suburban voters.

In 2022, Tory instead proposed that the province take over ownership of the city’s expressways — which is largely the way things work in the rest of Ontario. This, too, was nixed by the province. In fact, the portion of the Gardiner west of the Humber River was once owned by the province, but its hefty maintenance burden was downloaded onto the City in 1997.

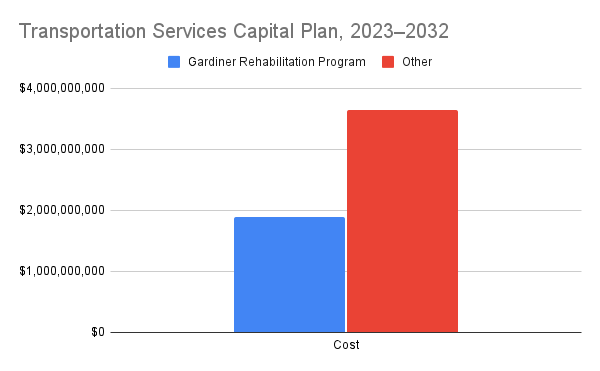

As it stands, the cost of rehabilitating and rebuilding the highway — $1.9 billion in total through 2032 — will come out of the regular municipal Transportation Services budget. It will comprise more than a third of total citywide spending on roads in that timeframe.

What’s next?

As it stands, the rehabilitation and reconstruction program is underway, and workers can be seen busily building as the highway meets the DVP. Given the sudden resignation of Tory, the project’s main champion, the Gardiner’s future may become an issue in the mayoral by-election.

Potential candidates, like Councillor Josh Matlow, have been seeking to reopen the debate on whether to demolish or realign the easternmost segment of the highway. Others, including some City staff, have argued that the project is too far along and nearly half of the billion-dollar cost of the realignment has already been spent or contracted.

As the mayoral election ramps up, Toronto’s longest landmark will loom over the race just as it does over the waterfront.

Gardiner construction photos courtesy of City of Toronto Archives

Code and markup by Chris Dinn. ©Torontoverse, 2023