How Toronto’s infamous Circus Riot exposed an unjust police force

As bizarre as it sounds, a heated 1855 brawl between firefighters and clowns ultimately led to important changes in the city.

On July 12, 1855, a fight broke out in a brothel near King and Jarvis (then known as Nelson) that ultimately led to major changes in Toronto policing.

On one side was a volunteer firefighter from one of the many autonomous groups that served Toronto in the absence of a centralized municipal force. (After all, the city had been formally established only 21 years earlier.) On the other was a clown.

The clown was part of an American touring group called S.B. Howes’ Star Troupe Menagerie & Circus. Newspaper reports claimed the fight started when a firefighter knocked a hat off the clown’s head and refused to apologize. The skirmish escalated into a brawl when their friends joined in, but ended quickly enough with the firefighters getting the worst of it.

That would have been the end of the story, if not for the Orange Order.

The Order is a Protestant British-unionist organization founded in Northern Ireland. At the time of the brawl, many of the city’s elite were members, including the police and firefighting groups — and they were fiercely loyal to one another.

The riot comes to the circus

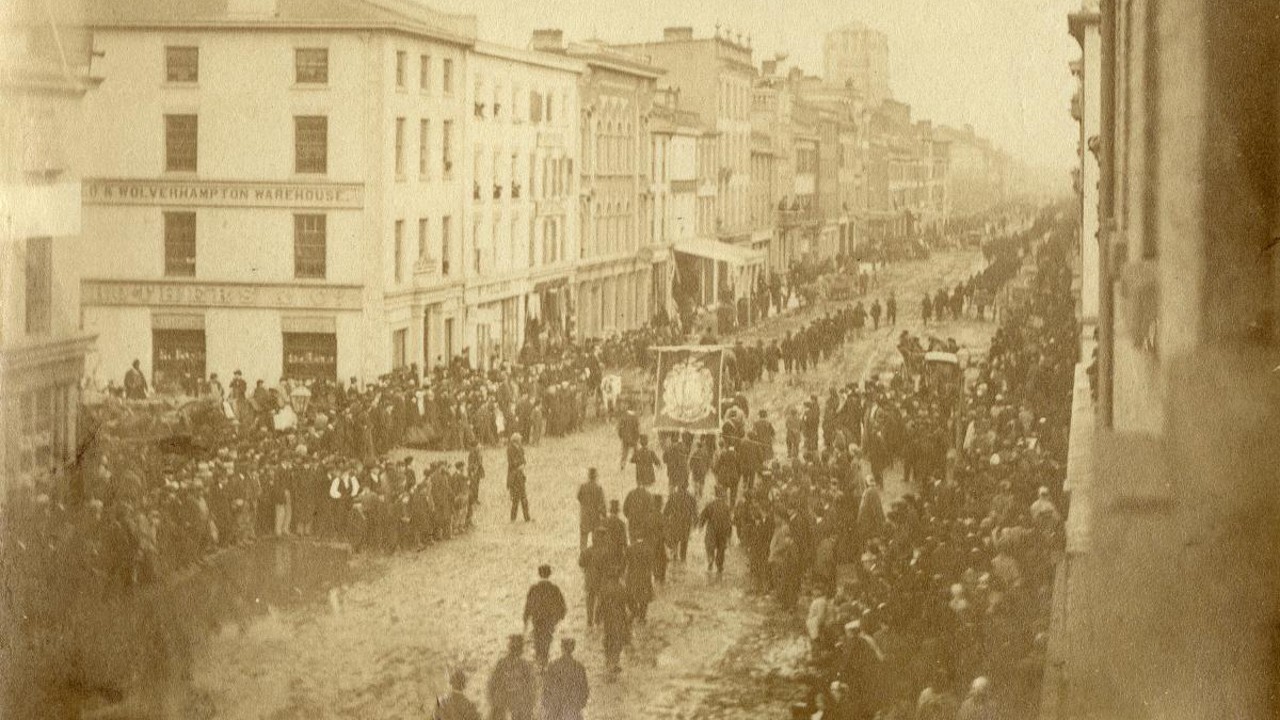

The night after the initial fight, a group of townspeople attempted to cut down the circus tent during the evening’s performance. When performers fought back, a much larger group of townspeople and firefighters descended on the green space near the city jail where the circus troupe was camped out.

Though there were at least a dozen constables on the scene, they failed to make any arrests. The circus performers were forced to run as rioters burned their belongings, overturned wagons, and pulled down the big top.

The scene became so violent that Toronto Mayor George William Allan himself arrived on scene and began to intervene. The Globe newspaper later praised his valour for stepping between the rioters and two imperiled circus performers, sending the would-be victims away in horse-drawn cabs instead:

“He spoke to the rioters singly and in groups, interposed between them and two of their destined victims whom they hauled out from the fallen tent, and were about to murder; and did all that magistrate could, who was utterly unsupported by a subordinate force.... There can be no doubt that but for the exertions of the Mayor, the lives of the circus men would have been sacrificed.”

Although the property damage was significant, no deaths were reported.

What happened next?

In the riot’s aftermath, chief of police Samuel Sherwood — an Orangeman who had publicly fought Irish Catholics himself in the past — was interrogated in court about the behavior of his men. He said it was difficult to identify who was doing what in the darkness, and by the same token could not order the arrests of anyone after the fact. Most of the other constables repeated his defense.

The favouritism was clear to everyone.

“How long will the City Council endure this infamous evasion of justice?” said a Globe report at the time.

Not for very long, as it turned out.

A January 1859 election brought in mayor Adam Wilson, who launched an inquest and had the entire police force fired. Although many constables were rehired, there were fresh recruits brought in from Britain and Ireland to dilute local prejudices. A new chief of police with military experience was installed to bring martial discipline to the force.

What began as a brothel brawl ended in sweeping legislative change. Thanks in part to the clowns, the Orange Order’s grasp over the city’s elite was broken.

This is an updated version of a story initially published in 2022.

Code and markup by Bridget Walsh. ©Torontoverse, 2023