Why GTA rental prices are returning to pre-pandemic peaks

Low inventory and sustained demand are driving increases, with other factors at play.

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Greater Toronto Area rental inventory skyrocketed as many city dwellers gave up their condos for greener pastures elsewhere, resulting in a massive decrease in rent prices.

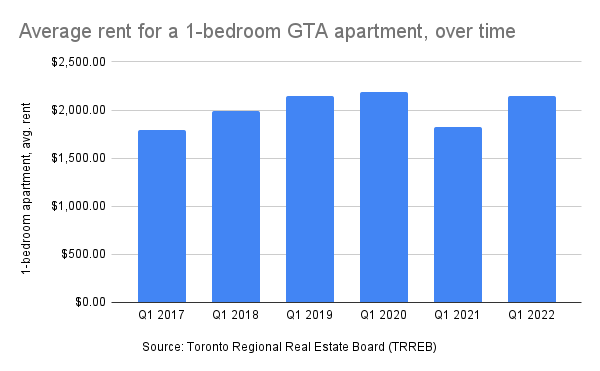

According to data from the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board (TRREB), which serves more than 66,000 brokers and salespeople in the GTA and Dufferin and Simcoe counties, the average price for a one-bedroom apartment in this region in the fourth quarter of 2020 was down 16.4 percent year over year. In Q4 of 2019, the average cost of a one-bedroom was $2,209 monthly — in 2020, it was $1,845.

Jason Mercer, the chief market analyst at TRREB, points to a shift in demand as the cause of lower rental prices during the pandemic. Not only were renters giving up their apartments in the city — investors and other owners who usually rent out their units on a short-term basis (as Airbnbs, for example) began putting them on the market as traditional long-term listings. This flooded the market with inventory, lowering prices dramatically.

“We had a situation where demand softened up at the same time that there were a lot of listings out there,” says Mercer, “so we could see rental fees trend lower.”

All of that, however, is steadily reversing.

According to Mercer, the big rental story of the latter half of 2021 and the early part of 2022 is the return to pre-pandemic prices.

TRREB’s 2022 Q1 report found the average rental price of a one-bedroom has soared up to $2,145, which represents a 17.8 percent increase year over year (a one-bedroom cost $1,820 in Q1 of 2021).

“We’re approaching that pre-pandemic peak,” Mercer says.

Lack of supply leading to rising prices

A big reason behind soaring rental prices is a steady drop in inventory — a reversal of the early pandemic’s over-saturated market. While TRREB reported a consistent level of demand year over year, the supply of available units dipped. The number of properties listed was down by almost 43 per cent in Q1, Mercer says.

(It’s important to note that TRREB tracks only listings reported through MLS, so their data will miss anything posted on sites like Facebook Marketplace or Padmapper, as well as places found simply through word of mouth. Plus, listings on MLS are typically condominiums, largely excluding basements, rooms in larger houses, and units with independent owners, which bumps up the average price.)

Of course, average rent prices vary by GTA region and municipality, and even among neighbourhoods within the City of Toronto. According to the latest numbers from Zumper, an online real estate platform, Trefann Court (the area just south of Cabbagetown) has the most expensive median rent, clocking in at $3,099 for a one-bedroom. Other pricey neighbouhoods include Old Mill ($2,500 for a one-bedroom), Rosedale ($2,400), Yorkville ($2,398), and Niagara ($2,300).

The neighbourhoods with the most affordable rents include Allenby, in the northwest of the city ($949 for a one-bedroom), Rouge in Scarborough ($1,000), and Harwood ($1,400).

And while larger trends can be hard to forecast, Mercer thinks that demand will stay high for rentals thanks to soaring interest rates, “which certainly impacts buying attention for first-time buyers,” he says. “If you’re putting your buying decision on hold, potentially because of higher borrowing costs, then you’d be more focused on the rental market.”

Plus, though immigration to Canada stalled during the pandemic and applications were backlogged, “we’re [now] seeing record levels of immigration into Ontario and a lot of that focused on the Greater Toronto Area,” says Mercer. “So that will also drive the demand for rental apartments moving forward as well.”

The future of affordable rentals

While all signs seem to point towards continued high prices for renters, there might be a small silver lining: The current climate might encourage builders to develop more units for the specific purpose of renting them out.

Unfortunately, creating these purpose-built units hasn’t been a priority for developers in recent years because the secondary market (as in, rental units put on the market by their owners) was “filling the void.” Plus, building and selling purpose-built units takes a lot longer than it does for traditional condominiums (around 10 years versus five to seven), because it’s easier to sell units to individuals than it is to management companies.

But now that the demand for rentals is sky-high, developers may turn their attention to purpose-built — which would mean some relief is on its way, even if that relief is still several years off.

“Pre-COVID, there were rumblings that rent levels had gotten to the point that some institutional players were looking at the prospects of bringing online some purpose-built rental,” says Mercer. “The impact of COVID put that kind of thinking on hold. So it’d be interesting to see rental market growth — we may see some players in the marketplace take a look at purpose-built again.”

Code and markup by Bridget Walsh. ©Torontoverse, 2022