What’s up with the Eglinton Crosstown LRT?

A visual explainer of the long-delayed (and potentially transformative) Toronto transit line.

The Eglinton Crosstown is the stuff of Toronto legend at this point, being the subject of an endless stream of news articles, talking-head discussions, and impassioned political speeches. But it may be helpful to step back for a moment and actually ask: What is it, why is it taking so long, and what will its impact be?

The Crosstown, which the Toronto Transit Commission (and probably most people) will refer to as Line 5 once it opens, is a 19-km “light rail transit” line that runs across Toronto along Eglinton Ave. Its history can be said to date back to the 1990s, when very preliminary excavation work began for a subway line along the street, but that project was cancelled with the election of premier Mike Harris in 1995.

It wouldn’t be until the “Transit City” plan emerged during David Miller’s mayoral tenure that the Eglinton line would reappear, this time as an LRT line.

What’s the plan for the Crosstown?

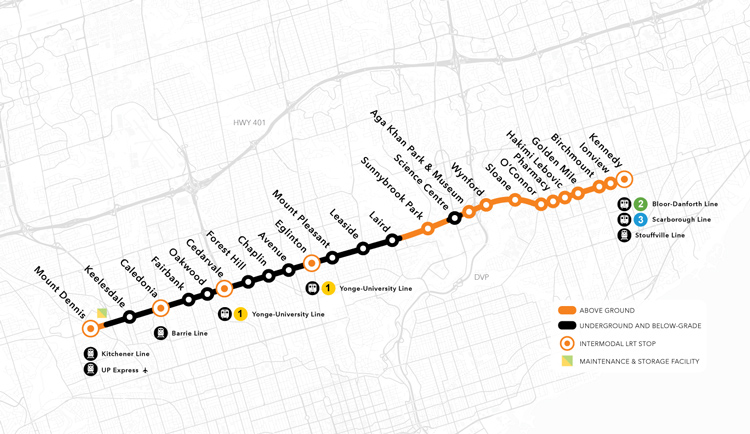

When it was officially proposed in 2007, the Eglinton-Scarborough Crosstown (as it was then known) was a 40-stop light rail line moving from Pearson Airport south to Eglinton Ave. and then across to Kennedy Station in Scarborough. While the centre section would be tunnelled, with large stations akin to what one expects on a more traditional Toronto subway line, much of the eastern and western extents were to be built at grade.

As of that initial plan, these eastern and western sections would closely resemble the 512 St. Clair streetcar route, with dedicated transit lanes, minimal surface stops, and some short “underpass”-like tunnels to allow for indoor interchange to other transit services at key locations such as Kennedy.

After a few years of debate, the project worked its way forward, albeit in a cut-down form that had it terminating just east of Weston Rd. rather than at YYZ — with a connection to the soon-to-be-upgraded GO Kitchener Line and UP Express to the airport. As of 2012, the estimated cost for the line was about $8.2 billion, and the province had committed $8.4 billion for its construction.

When it’s complete, the line will essentially consist of two distinct sections. Moving west from Laird Station, the Crosstown will mostly be deep underground in tunnels, which are notably even bigger than those used on the Line 1 subway extension to York University.

This section will feature 15 large stations with fully enclosed platforms, fare gates, and other related facilities — with all but the westernmost station at Mount Dennis being underground. This will leave users with an experience very much like existing Toronto subway lines.

To the east of Laird station, the line largely surfaces to run in the middle of Eglinton Ave., with more minimal surface stops tightly packed together. (In fact, the westbound platform of the Golden Mile stop is less than 100 m from the eastbound platform at the Hakimi Lebovic stop.) That said, there will be two more substantial underground stations at Don Mills and Kennedy to provide for interchange to Line 2 and the future Ontario Line.

Because of the limited capacity of the line on the surface — where, despite popular claims, trains may end up waiting for traffic lights — trains will operate less frequently than in the tunnelled “subway” section.

That said, the street-level section of Line 5 will introduce some nice quality-of-life features, including attractive grassy tracks, level boarding between trains and stops, and off-board fare payment points.

How has construction gone?

Now, when most people hear about the Eglinton Crosstown LRT, the first things they think about are delays and disruptive construction — so let’s talk about those.

Work on the project started in 2011, and was originally meant to be done by 2020.

However, major work on the large underground stations — the longest portion of the project’s development — didn’t start until 2016, after the Crosslinx Transit Solutions construction consortium earned the contract. This was already a few years after tunnelling work began, and extended timelines beyond the intended end point.

Also not helping things was the fact that the project changed hands from the City of Toronto to Metrolinx shortly before construction began.

As for the construction, a big reason it felt so disruptive is that the project simply impacts a huge swath of the city. The combination of underground construction on relatively narrow streets in Midtown Toronto along with tons of on-street work in Scarborough has made the project highly visible — and nigh unavoidable.

Another reason that construction even on the underground sections was so noticeable was that a lot of the work was not underground — instead, the plan involved the same cut-and-cover method used on older subways to excavate the stations.

What’s more, Eglinton Crosstown stations are often deeper and longer than older Toronto subway stations, with many having multiple entrances. This necessitated long construction zones, especially when you consider the space needed to manoeuvre and park equipment and store materials. Combine that with tightly packed stations in central parts of Eglinton, and construction felt like it was taking up the entire length of the street.

The good news is construction along much of the corridor is now totally complete, and what little material is left mostly exists for minor finishing works and blocking off the stations while the line is in testing phase.

The less-good news is construction isn’t the only element of the project. Eglinton line trains will use a rather complicated automatic train control signalling system from Bombardier. Getting it up and running will be further complicated by the fact that trains need to transition into and out of computer controller operations near Laird Station as they go from subway-style to streetcar-style running.

Because this is the first time these vehicles have ever been used with this signalling system, the testing process will naturally take longer than anyone wants. This is something that was seen with the Toronto-York-Spadina subway extension, where stations looked externally finished for almost a year before the project opened.

The amount of time this testing takes for the Crosstown depends on a number of factors, but most systems have to operate a “simulated service” with trains running as they would when the train will be open in order to be certified. This will likely mean running empty trains every few minutes for an extended period — usually a few weeks.

As for the big question: The line is expected to be finished and open sometime in 2023, but Metrolinx has not given an updated opening date in some time.

Finally, remember that $8.2-billion estimated cost from earlier? The latest estimates say the figure will be about $13 billion by the time the line’s finished. That said, this cost includes 30 years of maintenance for the line and vehicles, which will be operated directly by the TTC.

Will all of these headaches be worth it in the end?

So, with shovels mostly no longer in the ground, what will the Eglinton line bring to Toronto’s transit network? Well, in a word — connectivity.

Of the Crosstown’s 25 stations, five are existing stops that will now become interchange locations. These will likely be incredibly impactful, creating entirely new journeys that wouldn't have been practical before. For example, someone will now be able to take the Stouffville line from Markham to get to Sunnybrook Park, or take a comfortable ride from the Golden Mile in Scarborough to U of T’s St. George campus with just one transfer at Cedarvale station (formerly Eglinton West).

The Crosstown is also going to be Toronto's first step to being a truly polycentric transit city. Today, Toronto's rapid transit and rail systems are all incredibly downtown (or at least south-of-Bloor) centric, with the subway, streetcars, and GO trains all funnelling people into the old city of Toronto.

This has had huge impacts on the city, because it makes sense to build offices, university campuses, and more where people from all over the region can easily go. To a large extent the Crosstown will change that, making it just as easy for most of the region’s residents to get to Yonge and Eglinton as to Yonge and Dundas. It will also allow transit trips across the city that don't require venturing into the crowded downtown core.

What’s next?

With the construction wrapping up and excitement building for the central section of the Eglinton Line, in spite of the project's problems, the natural question is "Where do we go next?" And fortunately you don't have to look far for an answer.

As we speak, more tunnel boring machines are digging their way east from Renforth Dr. for a new seven-station, nearly 10-km extension of the Crosstown, which will eventually enable subway-style service direct to Pearson Airport and possibly even Mississauga City Centre. While megaprojects aren’t often predictable, it seems reasonable to expect that you could be riding a train from Scarborough to the western edge of the city by around 2030.

That said, there’s been controversy here, too, as some argue this could have been elevated rather than underground to maintain the subway-like speed without the high cost — based on the cost of elevated rail in other recent Canadian transit projects tunnelling the Eglinton west extension may have doubled the cost, which is nearly $5 Billion. But a grade-separated solution should at least ensure higher speeds, frequency, and reliability for riders.

The City of Toronto is also taking more modest steps to push forward the idea of an Eglinton Crosstown eastern extension, which would travel east from a terminal at Kennedy Station. Such a line would have some significant value in connecting the Lakeshore East GO line more directly to Midtown Toronto.

Suffice to say, a lot has happened on Eglinton in the past 10 years, and a lot more will happen in the next 10. But, in the end, the transformative effects of transit being built along the avenue will make the pain worth it.

Code and markup by Chris Dinn. ©Torontoverse, 2023