Why Toronto banned the St. Patrick’s Day Parade

A look at one of the most bizarre facts in our city’s history.

St. Patrick’s Day is coming up this week, which is an exciting time of year for me since I get to go around reminding everyone about one of the most bizarre facts in the history of our city:

The St. Patrick’s Day Parade was banned in Toronto for more than a century! It wasn’t allowed to return until the 1980s!

Why, you ask? Well, the answer involves religious hatred and sectarian violence. So, I thought I’d share the story I always like to share this time of year: the story of the days when our city was known as “The Belfast of Canada.”

Toronto was a very Irish place in the late 1800s. By the middle of the century, more than a third of our city’s residents had been born in Ireland — a higher percentage than even Boston or New York. Many of them were newcomers who’d been forced to flee the Great Famine and the hateful British policies that accompanied it. (In fact, many people prefer to call it “The Great Hunger” since “famine” makes it sound like a purely natural disaster.) In the summer of 1847 alone, nearly 40,000 Irish refugees came to Toronto — that was twice the population of the entire city at the time.

The vast majority of those new arrivals were Catholic. And they didn’t exactly find themselves welcomed with open arms.

Our city was VERY Protestant back then. Passionately, even angrily so. Not only were 75% of all Torontonians Protestant, many of them were members of the anti-Catholic Orange Order.

The Orange Order was founded in Northern Ireland in the late 1700s and it’s still a very big presence there to this day. Fiercely Protestant and vehemently anti-Catholic, it played a leading role in the violence of The Troubles; the annual Orange parades can spark riots even now. And while you don’t hear much about the group in Toronto these days, for a long time the Orange Order was the single most powerful organization in our city.

Orangemen kept a stranglehold on Toronto politics for a full century. From the middle of the 1800s all the way into the 1950s, nearly every single Mayor of Toronto was a member of an Orange Lodge. City councillors, too. Police officers. Firefighters. For a long time, practically all public employees were Orange. That meant that in the days when all those Irish refugees were pouring into the city, there wasn’t a single Catholic who held municipal office in Toronto. And for decades to come, well into the 1900s, Catholics had trouble getting hired for any public job in the city.

There was a time when prejudice against Irish-Catholics was a defining feature of life in Toronto. The Globe openly complained about their presence: “Irish beggars are to be met everywhere, they are as ignorant & vicious as they are poor. They are lazy, improvident, & unthankful; they fill our poorhouses & our prisons...” And the newspaper was hardly alone in its views.

Things got so bad that our city’s Catholic bishop began actively discouraging Irish-Catholics from moving to Toronto — warning them about the terrible discrimination they would face here.

And Orange power in Canada wasn’t limited to Toronto. It spread all over the country; you can find Orange Lodges from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island. At one point, there were more of them in Canada than in all of what’s now Northern Ireland. At the time of Confederation, a third of all Protestant men in Canada were, or had been, members of the Orange Order — including Sir John A. Macdonald — and it was said that the federal Conservatives always reserved three seats in their cabinets for Orange MPs.

But no city in Canada was more Orange than Toronto. And it was most often here that those sectarian tensions boiled over into violence.

The riots in Toronto often started with a parade — just like in Belfast. Every year on July 12th, the Orange Order would hold a big march to celebrate a victory from the 1600s — when Protestant King William of Orange won a battle against Catholics in Ireland. The “Twelfth” was practically an official holiday in Toronto. At its height, thousands of Torontonians marched in the parade. Tens of thousands cheered them on. Municipal employees got the day off with pay so they could attend.

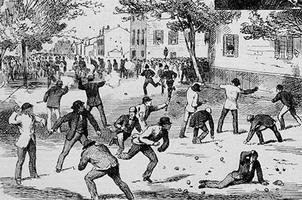

Catholics would generally stay indoors, keep their children close. But not always. The parades would occasionally erupt into violence between Orangemen and Irish Catholics, the battles of Belfast fought in the streets of Toronto.

Big Protestant vs. Catholic riots became almost an annual tradition in Toronto. Street battles broke out after political meetings and elections, when the Prince of Wales came to visit, on Guy Fawkes Day... Religious processions were attacked, St. Michael’s Cathedral besieged, the bishop pelted with stones... When a famous Irish Fenian revolutionary leader came to town, Orangemen rioted for two days. They smashed the windows of St. Lawrence Hall, destroyed a Fenian tavern and trashed stores on Queen Street. When Catholics celebrated the Papal Jubilee, stones rained down on them at Queen & Spadina. Thousands joined the fight. By the time it was all over, gunshots had been fired on Simcoe Street.

St. Patrick’s Day was especially tense in 1858. That’s the year Thomas D’Arcy McGee came to town to attend a banquet. He had once been a freedom fighter for Irish independence, a revolutionary who eventually moved to Canada and switched his allegiances. He was now a loyal British subject and would go on to become a Father of Confederation.

The violence that erupted around that year’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade ended with a Catholic stable-hand dead in the street. And his was certainly not the only life lost to the violence between Protestants and Catholics in Toronto. Even McGee himself would end up dead — gunned down in the streets of Ottawa. And the man who was hanged for the crime (after a travesty of a trial) was an Irish-Catholic suspected of having Fenian sympathies.

Heck, Toronto’s oldest public monument is dedicated to U of T students who died fighting Irish-Catholics — taking up arms when a Fenian army invaded Canada in the 1860s.

And so, in the wake of all that bloodshed, Toronto’s political leaders finally decided to do something to quell the violence. But they didn’t crack down on the Orange Order — of course they didn’t, they were all Orangemen themselves. Instead, they cracked down on the St. Patrick’s Day Parade. It was banned altogether. And would be for a very long time.

(The Orange Day Parade, on the other hand, continued on as a major public event. It’s still held today, in fact, in a much smaller form.)

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the Orange stranglehold on our city was finally broken. As Toronto began to evolve into a much more multicultural place in the wake of the Second World War, the demographics shifted dramatically. And for the very first time in the 118 years since the municipal government had been formed, the people of Toronto elected a mayor who wasn’t Protestant: Nathan Phillips was Jewish.

Even then, it would be another thirty years before Toronto decided it was safe enough for the St. Patrick’s Day Parade to return. It was in the 1980s that green-clad revellers took to the streets of our city to march in celebration for the first time in more than a century.

These days — in a non-pandemic year, anyway — it feels as if the whole city celebrates the holiday. And beyond a few drunken louts, there’s not a hint of the violence that once spilled blood in our streets.

Today, Toronto embraces its Irish heritage. And down on the waterfront, in Ireland Park, you’ll find a striking monument: a reminder of the Irish refugees who came to our city all those years ago… And of the contribution they and their descendants — Protestants and Catholics alike — have been making to Toronto ever since.

Code and markup by Kyle Duncan. ©Torontoverse, 2023